I first came across this play in the final moments of my teens thanks to a girlfriend I was besotted with, from Eastbourne. She had studied it (if I recall correctly) for A level. The play turned out to be one of those key texts which transformed my understanding of religion and psychology (and, on a side note, proving to be the only good thing that girl did for me in the end). But it’s been years since I’ve actually read the thing.

As the decades have gone on, I’ve found that, though life changes imperceptibly all the time, when you look at the texts you’ve been told all your life are classics, or go back to texts you thought were wonderful as a young man, you find yourself disappointed most of the time. Former heroes turn out to be charlatans; the heroes of others turn out to be lifeless and paper-thin in terms of depth. Life, it seems, has moved on a great deal more than you thought, but texts remain fixed in the time in which they were written. What was good ‘back then’ is rarely still good now. I get excited therefore when such a text emerges from my gaze either unscathed or at least still standing.

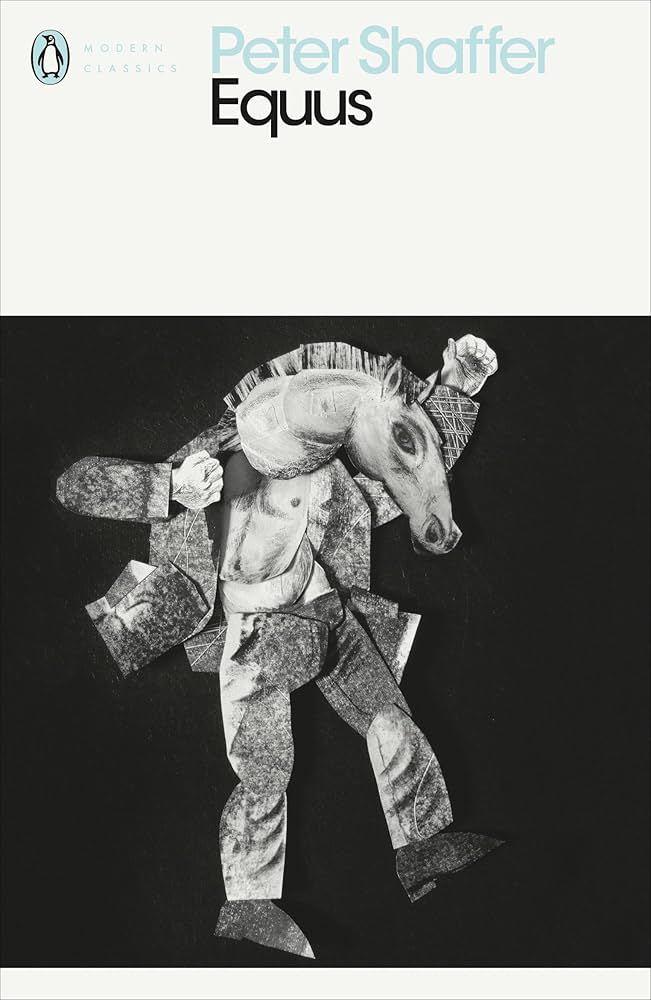

Peter Shaffer’s ‘Equus’ is one of the rare ones. It is not completely unscathed, I’ll admit – there are elements of pretensions in some of the monologues which grate a little – but the main body and drive of the story remain intact and relevant today.

The play is minimalist in style – effectively a boxing ring centre stage with the players sat around the outside, entering the ring only when they are playing their scene. Most objects are pretend. While the action is important it is actually what the characters are thinking which are most important. The horses are usually represented by wire-mesh heads and similar rather than descending into farce with panto-style costumes. Again, the horses are virtually unimportant in themselves – it is what they represent which is key.

According to the author, the story is based on a real-life event: a boy who stabbed out the eyes of several horses. Shaffer wanted to look at what would make a young man do such a cruel and evil thing. As all good plays should, the author succeeds in turning our expectations on their head and making us re-think what we take for granted.

Of course, religion is the focus (that was all but inevitable really wasn’t it?), but Shaffer takes a line which would have been ground-breaking at the time of writing but today reflects much of the angst of modern society. Society IS Dr Dysart now – lacking a faith in anything but feeling that lack as a result. In a post-9/11 world where the media caricatures faith as extremist and secularism as the sane and wisest choice, many are feeling that something is missing and thus sinking into despondency. Without God, Man becomes God – and that thought alone is depressing. No heaven, no future hope: this is as good as it gets.

In the 80s this play helped me understand the human condition where faith is absent. Today it helps me understand the extremist – not just the obvious so-called ‘Islamist’ ones, but the white supremacist who murders people in a black church, or the Buddhists in Myanmar murdering Muslim minority groups; or even the atheist who wants to censor and make illegal all religions. Understanding, of course, is not the same thing as condoning. Martin Dysart never condones the actions of Alan Strang, the youth who commits the bizarre atrocities against the horses he has loved and admired for so long, but he does come to be jealous of him and that jealousy comes from understanding where Alan has come from.

How Dysart makes this journey of understanding I’ll leave to you to find out from the play itself, but it is worth doing so, for – again in this post 9/11 world – we’ve never needed to understand the drives and motivations of so many people so much as we do now. Understanding allows us to communicate and communication allows reconciliation.

Is that the solution though? Dysart, once he gets to the bottom of Alan’s story, is left more disturbed than ever. Not with the boy but with himself and the culture he represents. Perhaps, in the end, understanding isn’t enough? It’s a bleak thought, but without finding out for ourselves we risk leading fantasy lives which leave us empty and without any hope at all.

My verdict:

Social Entrepreneur, educationalist, bestselling author and journalist, D K Powell is the author of the bestselling collection of literary short stories “The Old Man on the Beach“. His first book, ‘Sonali’ is a photo-memoir journal of life in Bangladesh and has been highly praised by the Bangladeshi diaspora worldwide. Students learning the Bengali language have also valued the English/Bengali translations on every page. His third book is ‘Try not to Laugh’ and is a guide to memorising, revising and passing exams for students.

Both ‘The Old Man on the Beach’ and ‘Sonali’ are available on Amazon for kindle and paperback. Published by Shopno Sriti Media. The novel,’The Pukur’, was published by Histria Books in 2022.

D K Powell is available to speak at events (see his TEDx talk here) and can be contacted at dkpowell.contact@gmail.com. Alternatively, he is available for one-to-one mentoring and runs a course on the psychology of writing. Listen to his life story in interview with the BBC here.

Ken writes for a number of publications around the world. Past reviewer for Paste magazine, The Doughnut, E2D and United Airways and Lancashire Life magazine. Currently reviews for Northern Arts Review. His reviews have been read more than 7.9 million times.

Get a free trial and 20% off Shortform by clicking here. Shortform is a brilliant tool and comes with my highest recommendation.

Leave a comment